Claws for Concern

Why my puns aren’t the only thing to watch out for this week….

We’re not hunting adversaries anymore Toto…

OpenClaw is having a moment, and I get why. A persistent assistant on your endpoint that can remember context, store credentials, and execute tasks without you babysitting it feels inevitable. For developers, it’s the logical next step in automation. For everyone else, it’s the logical next step in “how did this end up on my laptop?”

But the reason OpenClaw matters isn’t that it’s uniquely dangerous. It’s a clean example of a shift that’s been building for a while: endpoint risk moving from “malware” to capability misuse. This isn’t a product post. This is about operator reality: persistent agents with memory + identity + autonomous reach change your threat model, regardless of whether they arrived via a repo clone, a package manager, or a well-meaning employee trying to automate their day. And the best thing is…virality and adoption mean that change management isn’t really a thing when it comes to these sorts of applications.

Sydney Marrone (on my team at Nebulock) has a phenomenal write up in Hunt Mode, breaking down OpenClaw through behavior, with concrete indicators you can operationalize immediately. I’m not going to rewrite that post here. If you want the phase-by-phase breakdown and a quick reference table you can hand to your detection folks, go read Sydney’s write-up.

This ABCbyD post is the companion: how to think about this category and how to actually run it, so you’re not playing whack-a-mole with repos all year. Because you’re not hunting for persistence or lateral movement, you’re hunting capability in the wrong hands.

The category shift: from artifacts to operating models

Most endpoint programs are built around artifacts: hashes, file paths, known bad domains, specific process names. The security industry got really good at cataloging what malicious software looks like, and for a long time, that was the right strategy because adversaries reused the same tools and infrastructure. Artifacts were stable enough to matter.

Agentic tooling flips that model.

Framework names churn, repos move, binaries get renamed, packaging changes, and even when the tool is legitimate, the risk is contextual: the same agent that’s perfectly reasonable in a sandboxed dev environment becomes a problem when it’s sitting on a finance laptop with cached cloud credentials and a memory store quietly accumulating sensitive context.

So the control can’t be “detect OpenClaw.” That’s whack-a-mole, the control has to be “detect the operating model.”

Agentic frameworks need to do a few things to function:

arrive on disk somehow

create persistent state (memory/config)

often materialize identity (tokens/keys/profiles)

execute repeatedly, sometimes autonomously

reach out to services, APIs, and sometimes internal systems

Those aren’t brand-specific behaviors. They’re unavoidable mechanics. If you hunt names, you’ll always be late. If you hunt behaviors and sequences, you can catch misuse regardless of what the framework is called this week.

Where teams get fooled (and why this keeps happening)

The most common failure modes I’m seeing right now aren’t technical, but conceptual.

“It’s not malware, so it’s fine.” Wrong. Something can be non-malicious by design and still be high-risk in the wrong place with the wrong identity.

“We’ll block OpenClaw by name.” Fragile. You’ll block one repo and miss the fork, the rename, the vendored copy, or the agent embedded inside something else.

“It’s just dev tooling.” Sometimes…but “dev tooling” is not a free pass to store credentials locally, retain long-term memory of sensitive context, and execute actions autonomously on endpoints that were never scoped for that risk.

“We’ll wait for new signatures or the next (EDR) agent update.” You’ll be late, and even when a signature exists, it solves the wrong problem. You’re not trying to detect a specific tool. You’re trying to detect a capability showing up where it shouldn’t.

Static defenses built around artifacts wobble when the environment changes faster than your signatures do, and agentic tooling is just the newest proof.

Same tool, two totally different risk profiles

Here’s the simplest way I’ve been explaining this to teams.

A developer installs a persistent agent on a dev laptop, uses it to manage local environments, and it stores a limited-scope token for a non-production service. You can observe it: it stays in its lane, and that might be completely fine.

Now take the exact same operating model and put it on the wrong machine: an executive laptop or a finance workstation. It creates a user-scoped hidden directory, starts accumulating memory (context from documents, tickets, emails, whatever it’s fed), and someone drops a broadly-scoped API token into its config because “it kept failing without it.” The agent runs again, reads the token, and starts making API calls the user has never made before because the agent is exploring and optimizing.

Nothing about that requires “malware.” No exploit, implant, or dropper. Just capability in the wrong hands, placed in the wrong context, with identity it should never have had. This my friends is why OpenClaw matters. Not because it’s special, but because it makes the shift obvious.

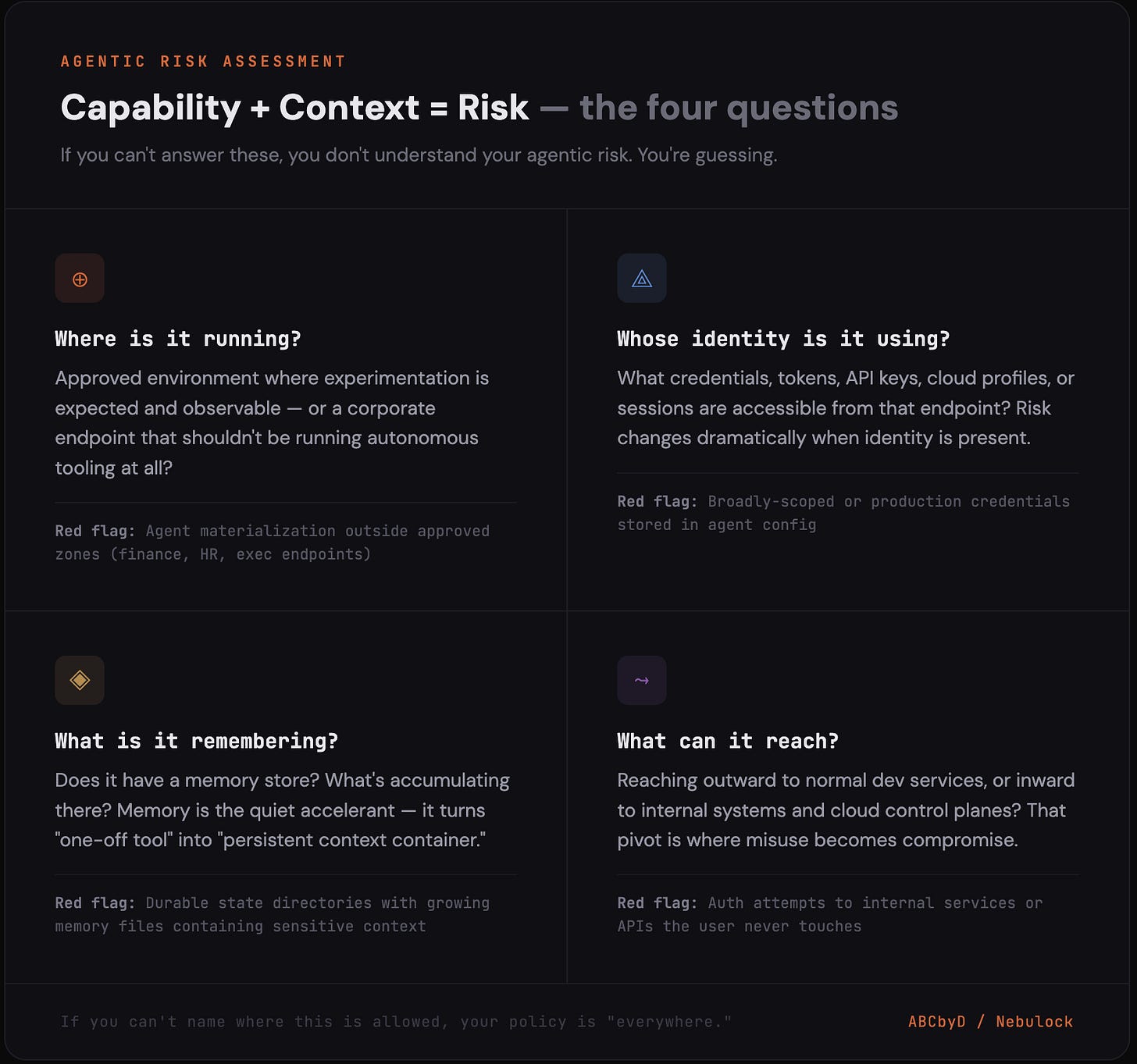

Capability + context = risk (the four questions)

When you find something like OpenClaw, or any persistent agent framework, ask four questions:

Where is it running? Is this an approved environment where experimentation is expected and observable, or a corporate endpoint that shouldn’t be running autonomous tooling at all?

Whose identity is it using? What credentials, tokens, API keys, cloud profiles, or sessions are accessible from that endpoint? The risk profile changes dramatically when identity is present.

What is it remembering? Does it have a memory store? If so, what’s accumulating there? Memory is what turns a one-off tool into something that knows too much. That’s the part most teams miss.

What can it reach? Is it reaching outward to normal dev services, or inward to internal systems and cloud control planes? The pivot from “external automation” to “internal reach” is where misuse becomes compromise.

If you can’t answer those four questions, you don’t understand your agentic risk, you’re guessing…and if you can’t name where this is allowed, your policy is effectively “everywhere,” and that’s not a policy.

These questions in Matrix form for copy/paste ease…

The Monday plan: what we should do this week

When this lands in the real world, it doesn’t land as an alert called “agentic misuse.” It lands as a weird install event on a laptop you didn’t expect, followed by a new hidden directory in a user profile, followed by a process tree you’ve never had to care about before.

Here’s how I’d run this as a one-week sprint.

Step 1: Draw the boundary (approved zones vs. drift)

You don’t need a perfect policy. You need a line in the sand.

Start by defining where agentic tooling is acceptable by default. Most teams land on some version of:

Approved: dev laptops, engineering VDI pools, lab machines, sandbox hosts you can observe

Not approved (initially): corporate endpoints outside engineering, production servers, high-sensitivity user groups (finance, HR, exec), anything that holds privileged identity by default

If you’re unsure, start conservative. Allow in engineering environments you can observe, and treat everything else as drift until you intentionally expand. This is the decision that makes everything else sane, and without it, every finding becomes an argument.

Step 2: Watch for materialization (install + state + first execution)

Your first detection layer shouldn’t be “OpenClaw executed.” It should be “agentic tooling showed up.”

Agents can arrive a dozen ways, but the mechanics don’t change:

interactive package manager installs (pip/npm/etc.)

git clones into user directories

creation of user-scoped hidden state directories that persist (config + memory)

first executions out of home directories or project paths

One concrete example, without turning this into a brittle signature: look for new hidden directories under user profiles that contain durable state (memory files, config JSON, auth/profile artifacts) created shortly after an interactive install or clone. Most tools create config. Fewer create long-lived “memory + identity” stores unless they’re built to act autonomously.

If you have basic EDR telemetry (process exec, command line, parent-child, file create/write in user directories), you can do this today. The output should be boring: a daily list of “new agent-like materialization,” enriched with endpoint class and user role.

Step 3: Classify, then convict with behavior chains

This is where teams either overreact or ignore everything. Don’t do either.

Classify using who + where + what:

who ran it (developer, SRE, finance, HR)

where it ran (dev fleet, corporate fleet, servers)

what toolchain is normal on that endpoint (python/node present or not, typical install cadence)

Then bucket into three categories:

Expected: dev user on dev endpoint, within approved zones

Unexpected: non-dev user or non-dev endpoint

Concerning: unexpected plus signs of identity materialization, persistence, or internal reach

Now the conviction piece. Conviction should come from sequences, not single events. Here are two chains you can run without relying on framework names.

Conviction chain A: state + identity (the accelerant)

Plain-English logic:

A new user-scoped hidden state directory appears (agent-like config/memory store).

A credential-like artifact appears inside it (tokens, profiles, keys).

That identity is accessed in a way that doesn’t match expectation: unusual parent process, non-interactive access, or rapid access immediately after creation.

Why this convicts: The risk shift happens when the endpoint becomes a credential container for an autonomous system. That’s when “tool” becomes “capability.”

→ The signal: if an agent is storing credentials it didn’t need, something already went wrong.

Action when it hits:

Identify the scope of the identity (what services can it reach?)

Revoke/rotate if it’s privileged or out of policy

Pivot to cloud/API audit logs to validate what it actually did

Escalate based on endpoint class (dev sandbox ≠ finance workstation)

Conviction chain B: execution + internal reach (the pivot)

Plain-English logic:

Agent-like execution occurs (interpreter launching code from home/project paths), repeatedly or shortly after install.

Within minutes, you see systematic exploration. Identity checks, hostname, environment inspection, broad file discovery.

Within the same window, outbound authentication attempts to internal services or cloud control planes (SSH, internal APIs, cloud CLIs), especially to targets the user doesn’t normally touch.

Why this convicts: It’s the moment the agent moves from “helping me do a task” to “operating in my environment.” On the wrong endpoint, that’s unacceptable even if intent started benign.

→ The signal: if an agent is authenticating to services the user never touches, that’s not automation. That’s drift.

Action when it hits:

Contain or restrict network access if outside approved zones

Validate targets touched (internal auth logs, cloud audit)

Treat it as a misuse investigation, not “malware cleanup”

These sequences are the durable control. Names change. Chains don’t.

Step 4: Baseline the benign and put guardrails around identity

This is how you stop playing whack-a-mole.

Once you’ve defined zones and you’re classifying consistently, baseline what “normal” looks like inside the approved areas:

install patterns (who installs, how often, from where)

execution patterns (which interpreters, from which parents, from which paths)

expected egress for dev tooling (package registries, code hosting, sanctioned SaaS)

Then flag drift:

agent-like state directories outside approved zones

long-lived tokens created or used from endpoints that shouldn’t hold them

internal network touches clustered immediately after agent execution

persistence mechanisms pointing at user-scoped agent code

And here’s the control that matters most: identity guardrails. If agentic frameworks are “one configuration file away from insider risk,” identity is the configuration file. Shorten token lifetimes where possible. Scope them tightly. Restrict where production-grade credentials can live. Monitor token creation and unusual token use from endpoints.

You can’t prevent every tool from appearing, but you can prevent tools from having god-mode when they do.

Education, without punishing curiosity

This category is going to show up as “shadow deployment” long before it shows up as “breach,” which means education matters.

Keep the message simple:

Agentic tooling is allowed in approved zones

Don’t store production credentials locally

If you need agentic tooling, here’s the sanctioned workflow

If you see it on a non-approved machine, report it quickly

You’re not trying to ban productivity. You’re trying to keep capability bounded and observable.

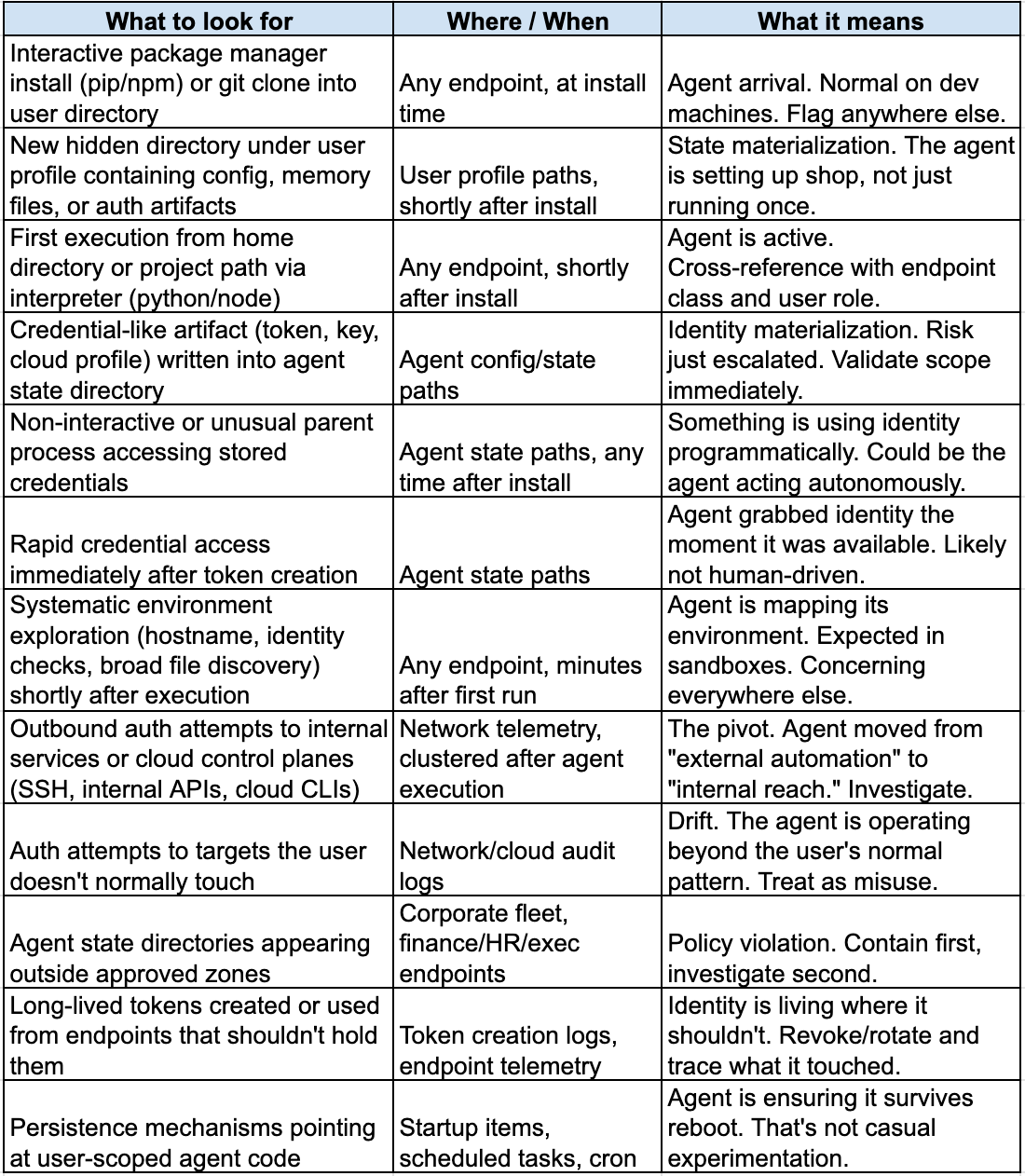

Quick reference: behavioral indicators across the agentic tooling lifecycle

Why this matters beyond OpenClaw

OpenClaw is an example. The next framework will have a different repo and a different name. What won’t change is the operating model.

Sydney’s write-up gives you the tactical breakdown: the behaviors and phases you can hunt today, regardless of packaging. This post is the companion. Draw the boundary, watch for materialization, classify by context, convict through behavior chains, baseline the benign, and put guardrails around identity.

You’re not hunting OpenClaw, you’re hunting capability in the wrong hands.

Stay secure and stay curious, my friends.

Damien

Strong take on hunting operating models instead of artifacts. The conviction chains around identity materialization make alot of sense, especially when most teams are still thinking signature-first. I've been seeing similiar patterns with credential sprawl once agentic tools land on endpoints they weren't scoped for.

Great write-up Demian!! To help contain OpenClaw to begin with, we open sourced an OpenClaw guardrails extension that uses policy as code to block/steer unwanted behavior and prevent things like rm -rf, sudo, or leaking secrets. More here:

https://securetrajectories.substack.com/p/openclaw-rm-rf-policy-as-code