MITRE ER7 Eval Demystification Part 1: The Mental Model

Cloud's in - this will be good

“When a real-world style intrusion unfolds, what does this tool actually surface, at what fidelity, and how much work does it push onto my team to understand what’s happening?”

Happy New Year ABCbyD community! Between the holidays and a fast start to the year, it’s been a minute - thrilled to be back in the saddle and we’ve got a four parter to kick the year off. Welcome back…let’s talk MITRE ATT&CK evaluation, the annual scoreboard that’s really not supposed to be a scoreboard.

Jokes aside, the problem is not that vendors market, it’s that the marketing language is almost never the language an operator needs. “100% detection” does not tell you what you will see in your console when the intrusion is unfolding. “Zero false positives” does not tell you whether the system is producing crisp, high-context narratives or vague signals that your team will translate manually at 2am.

If you want ER7 to be useful, you have to treat it like evidence, not like a ranking. MITRE is explicit about this: the Enterprise 2025 round is published as objective, evidence-based results, and the program does not rank vendors. That framing is not a legal disclaimer, rather It’s an instruction for how to read the artifact.

This post is Part 1 of a four-part series. Why a four part series about an eval that happened a month ago? There’s a lot to unpack, and given the comprehensive nature of this eval (and the very real implications for operators), I’d like to be thorough and ultimately give y’all the means with which to action this evaluation, rank and stack the vendors, and go hunting for adversaries in your backyard. The goal here is not to grade vendors, but to build the mental model that keeps you from being manipulated by charts, and helps you extract something practical from the dataset. We’ll get to tiering, scoring, and cloud hunting soon. But first we need to agree on what ER7 is, and what it is not.

What ER7 is (and what it isn’t)

ER7 is a structured record of what MITRE observed when participating vendors ran their tools in a defined environment against adversary-inspired scenarios. The output is decomposed into steps and substeps, mapped to ATT&CK, and published so you can interpret it for your own context.

If you’ve ever done a purple team exercise and wished you could compare how different tools surfaced the same behavior sequence, ER7 is the public version of that idea. The difference is, it’s performed in a highly structured, specific environment that MITRE is transparent about, should you choose to replicate it.

That being said, this is not your environment, identity posture or cloud config. It’s not your data quality. It’s not your analysts, your playbooks, your escalation culture, or the way your business reacts when something gets blocked.

So ER7 is not a proxy for “best product.” It’s a dataset that can help you answer a narrower, more operator-relevant question…

“When a real-world style intrusion unfolds, what does this tool actually surface, at what fidelity, and how much work does it push onto my team to understand what’s happening?”

That question is what makes ER7 worth reading, and it’s also the question that vendor scoreboards rarely answer, because it is hard to market “we reduced analyst translation work by 40%.” Instead we get victory lap language that flattens nuance and hides tradeoffs.

Why ER7 is different this year

ER7 is one of the more meaningful shifts in the Enterprise evaluation series, because MITRE changed the shape of the test in ways that align with modern breach reality.

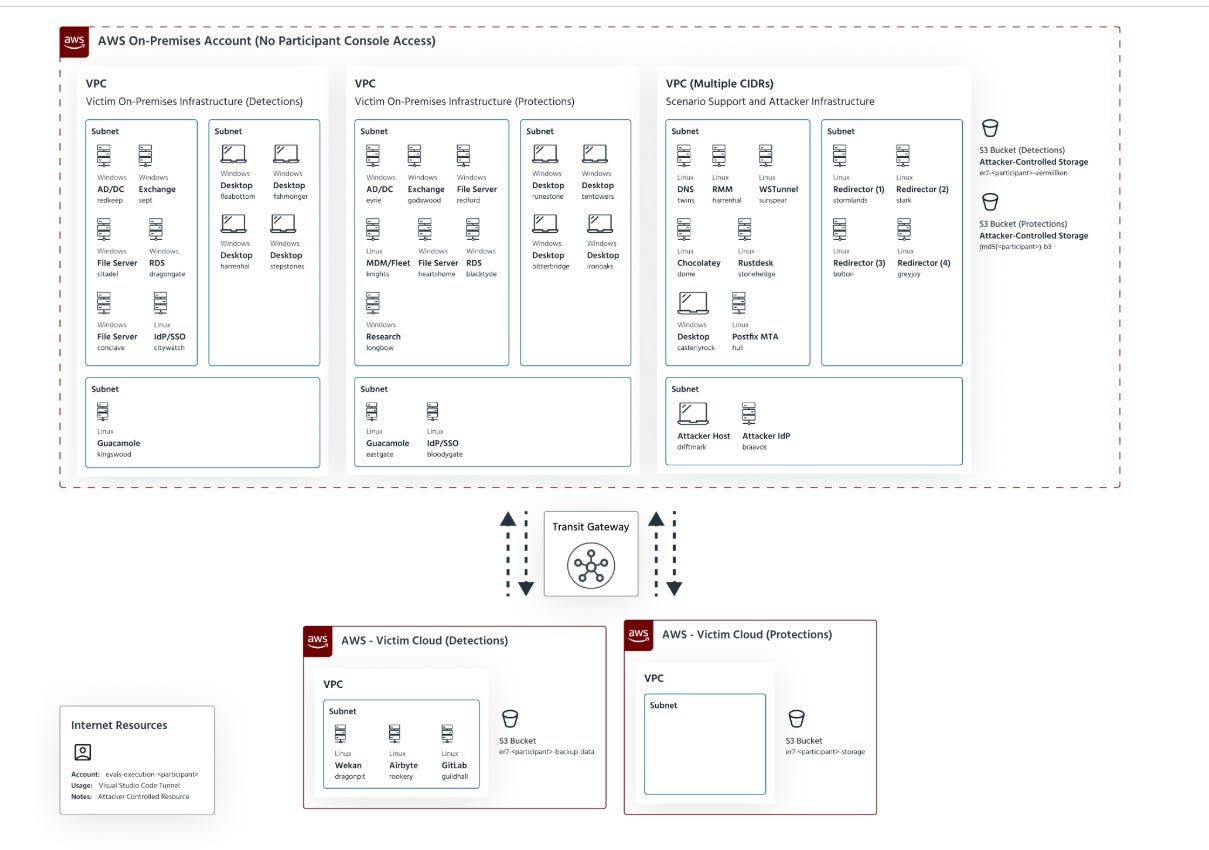

Screenshot of Test Environment

First, MITRE describes Enterprise 2025 as focusing on detection of and protection against cloud-based attacks and abuse of legitimate tools and processes. That is the closest I’ve seen the evaluation come to stating the reality of breaches today: the intrusion path is now cross-domain by default. Attackers don’t “live” in your endpoint. They live in your identity plane, your control plane, and whatever legitimate tools your organization uses to run the business.

Second, ER7 led its first-ever cloud adversary emulation. Not only is this awesome to see, but it matters because “cloud” has been a supporting character in too many evaluations and too many security programs. Cloud is not a log source you onboard after your endpoint program is “done.” It’s primary terrain and for almost every organization out there today, it is the terrain.

Third, Reconnaissance was incorporated as a tactic for the first time in these enterprise evals. That sounds like taxonomy trivia until you reflect on what it implies operationally. The evaluation is acknowledging that early-stage visibility matters. If you only surface the intrusion after persistence or staging, you are detecting late. Late detection can still reduce harm, but we should stop pretending it is equivalent to early warning.

…and finally, MITRE explicitly frames the updated reporting focus around detection quality, alert volume management, and protection strategies that matter most to organizations. Translation: they are trying, imperfectly but intentionally, to move this away from “did it alert at all” and toward “did it help an operator.”

The two scenarios: two different operator problems

ER7 is built around two adversary-inspired scenarios: Scattered Spider and Mustang Panda. These are not interchangeable. They exercise different muscles and they should change what you look for when you read results.

Scattered Spider is the one most modern defenders should start with, especially if you are cloud-first and identity-centric. MITRE’s own messaging around Enterprise 2025 highlights cloud infrastructure and financially motivated threats as central themes. This scenario is designed to reflect a breach pattern we keep seeing: social engineering and identity abuse, then rapid movement through control-plane operations and legitimate tooling, then data movement that can blend into normal business behavior if you don’t have baselines.

Mustang Panda is a different story. It’s counter-espionage flavor, with tradecraft that can include stealth, persistence, and custom tooling. Both are real. Both matter. But if you read ER7 like “coverage across everything,” you’ll miss the more useful framing: each scenario is a lens, and the right lens depends on what keeps you up at night.

MITRE publishes technique scope for both scenarios. Those numbers can be tempting, and people (myself included) love to count. But the count is not the point. The point is whether the tool helps you understand the story at the moments where the intrusion could still be interrupted.

Decision points. That’s the concept we’ll use in Part 3 when we turn the cloud scenario into hunt hypotheses and baselines. For now, just hold the frame: ER7 is telling two stories, and you should read them as stories, not as tallies.

Participation: what it does and doesn’t prove

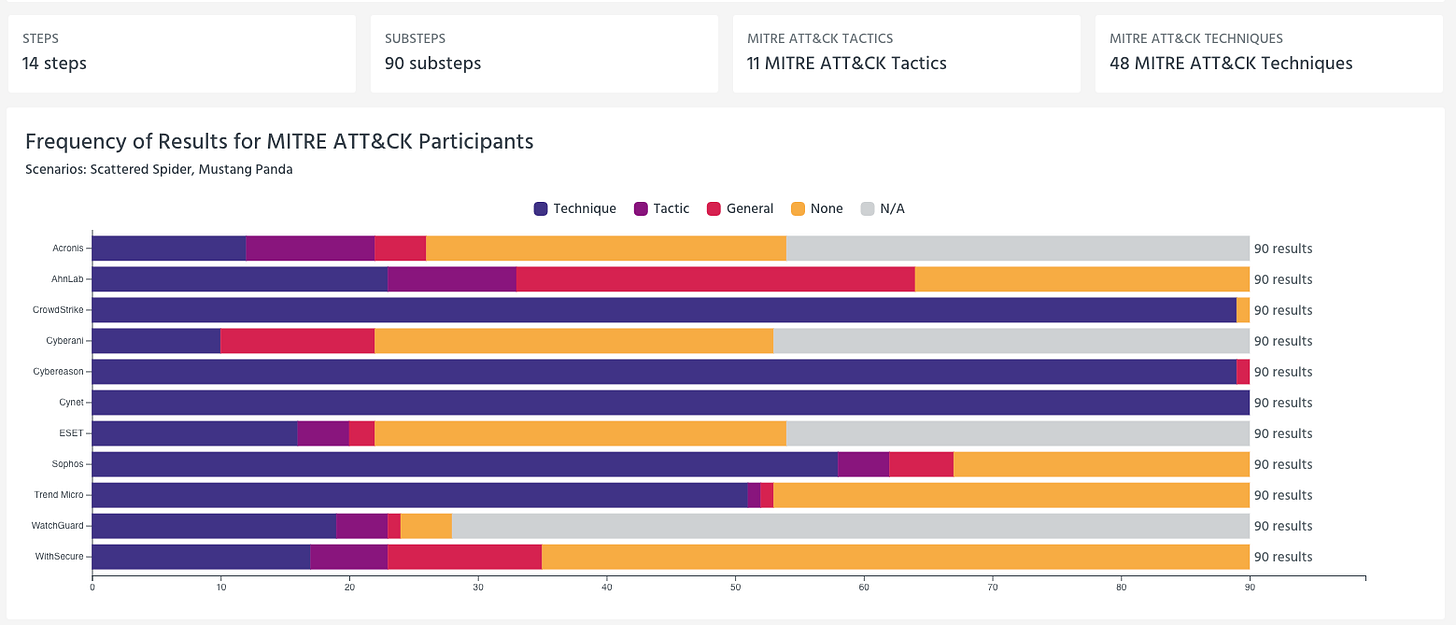

This year’s cohort includes 11 participants:

MITRE’s ER7 Cohort

Participation matters, but not in the simplistic way social media likes to imply. Showing up does not make a tool “best.” Not showing up does not make a tool “bad.” This program is resource-intensive, and some vendors publicly stated they chose not to participate in this cycle.

Palo Alto Networks framed its decision as focusing effort to accelerate innovation for customers. SentinelOne said it wanted to prioritize product and engineering resources on customer-focused initiatives and accelerate its roadmap. Microsoft, after deliberation, also chose not to participate.

Operators should take a sober view here. Non-participation is not a technical result, but it does create a comparability gap. It also creates narrative space for the vendors that did participate. The cohort is not “the market.” It is “the market that showed up,” and the dataset should be treated accordingly.

If you want to be disciplined about it, here’s my suggested take: participation gives you a public evidence trail you can interrogate. Non-participation means you need to validate through other means: internal testing, breach simulations, vendor references, and deployment in your own environment.

How to read ER7 pragmatically

If you only remember one thing from Part 1, remember this: the unit of truth in ER7 is not the vendor blog post, and it is not the cohort graphic. The unit of truth is the step and substep record.

MITRE’s results portal gives you a cohort view for a scenario like Scattered Spider that shows 7 steps and 62 substeps, along with the distribution of detection categories across participants. That’s helpful for seeing where tools diverge, but it’s still a macro view. The real value comes when you click into the substeps and (importantly) treat them like a timeline.

Results Portal Screenshot

This is where operators can get leverage, because you can stop asking “did it detect” and start asking “what did it detect, how did it express it, and what work did it create for my team.”

MITRE categorizes detection results into buckets like Technique, Tactic, General, None, and N/A. The industry loves to debate these categories abstractly. I prefer to translate them into practical experience.

Technique detections are closest to what a defender needs because they tend to map to behavioral specificity and reduce translation work. If you are building a program that needs repeatable, understandable detections that can be operationalized, Technique-level signal matters.

Tactic detections can still be useful, but they often force you to do more correlation work. “This looks like Discovery” is less helpful than “this looks like this specific discovery behavior and here is the evidence.” If your team is strong and well-staffed, you can absorb that translation. If you are lean, tactic-level signal often becomes toil.

General detections are where you need to be honest. “Something suspicious happened” may be enough to trigger investigation, but it is not the same thing as a high-context detection. If an evaluation record is heavy on General detections, what you’ve learned is that the tool is pushing meaning-making onto your analysts.

None means no surfaced alert. That doesn’t necessarily mean no telemetry existed in the environment. It means the product did not produce something that an operator can use in the moment. That is an important distinction, because it changes the burden from detection to hunting. If you’re comfortable living in hunt mode, you can still win. If you’re depending on the product to surface the moment, None tells you something.

N/A is scope and constraints. It’s not a miss, and it’s not a win. Treat it as “not demonstrated.”

Once you internalize that these categories map to workload, you stop caring about “100% detection” headlines and start caring about distribution and context. A tool with broad “General” coverage can still claim success while creating a painful operational reality. Coverage without fidelity is workload.

Now the second thing you must train yourself to look for are the modifiers that change interpretation.

MITRE’s portal includes modifiers like configuration change and delayed detections. Configuration change is not inherently bad. Tuning is real. But it changes what you are measuring. Initial run performance is closer to day-one reality. Configuration change performance is closer to day-n reality after iteration and tuning. Those are different cost curves, and they should not be collapsed into a single “score” without telling the reader what you value.

Delayed detections are similar. Some analytics are retrospective by nature. That can be perfectly fine for certain stages of an intrusion, but not for others. A delayed detection about recon or discovery might still be useful as a hunting lead. A delayed detection about staging or exfiltration is a postmortem…again, context matters.

This is why I’ve been referring to ER7 as a breach trace in discussions I’m having. If you read it like an incident timeline, you naturally ask timeline questions: when would my team know, how would they know, and would they understand what they were seeing.

Protection: don’t oversimplify “blocked”

ER7 also publishes protection results, and protection is the easiest place for marketing to oversimplify. “Blocked” feels like a win because it is binary and easy to understand. But protection is only valuable if it stops meaningful parts of the chain without breaking legitimate operations. Over-blocking creates outages, and outages train the business to route around security. That is how you lose long-term.

MITRE explicitly calls out that the focus includes protection strategies that matter most to organizations. That is an invitation to read protection as an operational tradeoff, not as a trophy.

We’ll do protection properly later in this series. For Part 1, I just want to set the expectation: prevention without operational discipline becomes self-harm. The eval contains enough nuance to see hints of that, but you have to look past the binary.

Where we go from here…

Part 1 is the mental model. ER7 is evidence, published as a structured breach trace across two scenarios, with a meaningful shift toward cloud and toward operationally relevant reporting. If you read it like a scoreboard, you’ll learn almost nothing. If you read it like a timeline, you can learn how products express behavior, how much context they provide, and how much translation work they hand to your team.

In Part 2, we’ll get concrete. I’ll walk through how I interpret detection results in a way that maps to operator reality, and I’ll introduce a tiered rubric. Not “best product,” but “best fit under a clear operational lens.”

In Part 3, we’ll focus on what I think is the most valuable part of ER7: the cloud scenario. We’ll turn it into a hunting playbook, with hypotheses and baselines derived from the scenario’s decision points.

In Part 4, we’ll do the thing everyone asks for and most people do un-objectively: scoring. I’ll build a simple, transparent model that weights technique fidelity, alert volume and narrative clarity, configuration dependency, and protection behavior. The weights will be explicit, and so will the bias, because the moment you score anything you’re encoding values. Then we’ll flip it into a hunt-first approach that turns evaluation gaps into a backlog you can actually run.

Happy belated new year, 2026 is off and running, and with that…

Stay secure and stay curious, my friends.

Damien